Steven Porges' HRV Journey

- Fred Shaffer

- Dec 6, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2025

This post is based on Steven Porges' (2022) inspiring account: "Heart rate variability: A personal journey," published in Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

A Living Signal, Not a Metronome

Heart rate variability, usually shortened to HRV, is the moment-to-moment variation in the timing between heartbeats. It is not a mistake in the system. It is a living signature of how the nervous system is regulating the heart in real-time.

In Stephen Porges' account, HRV becomes more than a measurement. It becomes a lifelong portal into theory, mechanism, and clinical possibility, pursued across seven decades of research and reflection.

That "portal" language matters. It suggests a disciplined humility: start with what the body is already doing, measure it carefully, and let the pattern teach you what questions are worth asking. Porges' career, as he tells it, is a sustained demonstration of how patient measurement can grow into a generous theory of human regulation.

The Graduate Student, the Paper Trace, and the Surprise

Porges' journey opens in the late 1960s, when psychophysiology, the field that links psychological processes with measurable physiology, was still defining itself. In that early phase, he was already chasing a bold question with a practical route: could mental effort be detected without asking people to explain themselves, simply by listening to the body?

The scene is wonderfully concrete. He watches beat-to-beat heart rate on polygraph paper and notices something that does not fit the expectations of the time: during sustained attention tasks, the heart rate pattern becomes more stable, then later returns to a rhythmic baseline that seems tied to breathing. Today we might describe this as a shift in the respiratory-linked component of HRV, but at the time it was an empirical surprise, not a named phenomenon.

What follows is an early glimpse of Porges' signature style: curiosity paired with engineering-minded rigor.

He and his mentor, David Raskin, immediately ask whether breathing is mediating the effect, realize they cannot answer without measurement, and pause the experiment to add a respiration sensor to the Dynograph, a physiological recorder used to track signals in real time.

A Beckman Dynograph is shown below.

This is how careers quietly become foundations. A new observation appears on paper. The researcher does not rush past it. Instead, instruments are upgraded, assumptions are tested, and a phenomenon begins to acquire both definition and meaning.

Measuring Under Constraint, Thinking Without Shortcuts

It is hard not to admire the persistence required by the technology of the era. Before lab computers, data reduction was physical labor. Porges describes measuring tracings with a millimeter ruler, recording values in a notebook, then punching cards and carrying stacks of them to a mainframe for analysis. The workflow had built-in risk: an error printout could cost days.

That constraint shaped a research temperament. When measurement is hard, you learn to respect every variable and distrust vague interpretation. It also clarifies why Porges repeatedly returns to methods.

In his telling, theory does not float above data. Theory is filtered through what can be measured with validity, especially when the goal is to link body regulation to attention, emotion, and health.

The early payoff was striking: HRV, not just average heart rate or breathing rate, was uniquely sensitive to attention demands, with mental effort linked to suppression of HRV. That finding set a theme that runs through his narrative: meaningful physiology often lives in patterns, not averages.

From "How Variable?" to "Variable in Which Way?"

Quantification is where Porges' influence becomes field-shaping. He distinguishes between two broad approaches: descriptive statistics such as range or variance, and modeling the heart rate pattern to extract variance components tied to known physiological mechanisms. That second approach is where HRV becomes interpretable in mechanistic terms.

Time series methods, including spectral analysis, treat a physiological signal as a sequence over time and examine its rhythms. Spectral analysis is a way of asking: how much of the variability occurs at different frequencies, including the breathing frequency? Porges did not only adopt these methods; he actively disseminated them, organizing symposia and workshops that helped bring time series thinking into mainstream psychophysiology.

He is also notably careful about what HRV can and cannot claim. A popular assumption in some HRV work is that slower frequency components or ratios can index sympathetic activation or an overall "sympathovagal balance," meaning a tug-of-war between sympathetic and parasympathetic influences.

Porges argues that there is no reliable evidence that these slower frequency components, or their ratios with respiratory-linked variability, provide a direct index of sympathetic activity. This is not mere methodological quibbling. It is a principled insistence that interpretation must track physiology, not convenience.

Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia, the Vagus, and a Noninvasive Window

A central character in Porges' story is respiratory sinus arrhythmia, or RSA.

RSA is the rhythmic speeding and slowing of heart rate that occurs at the frequency of breathing.

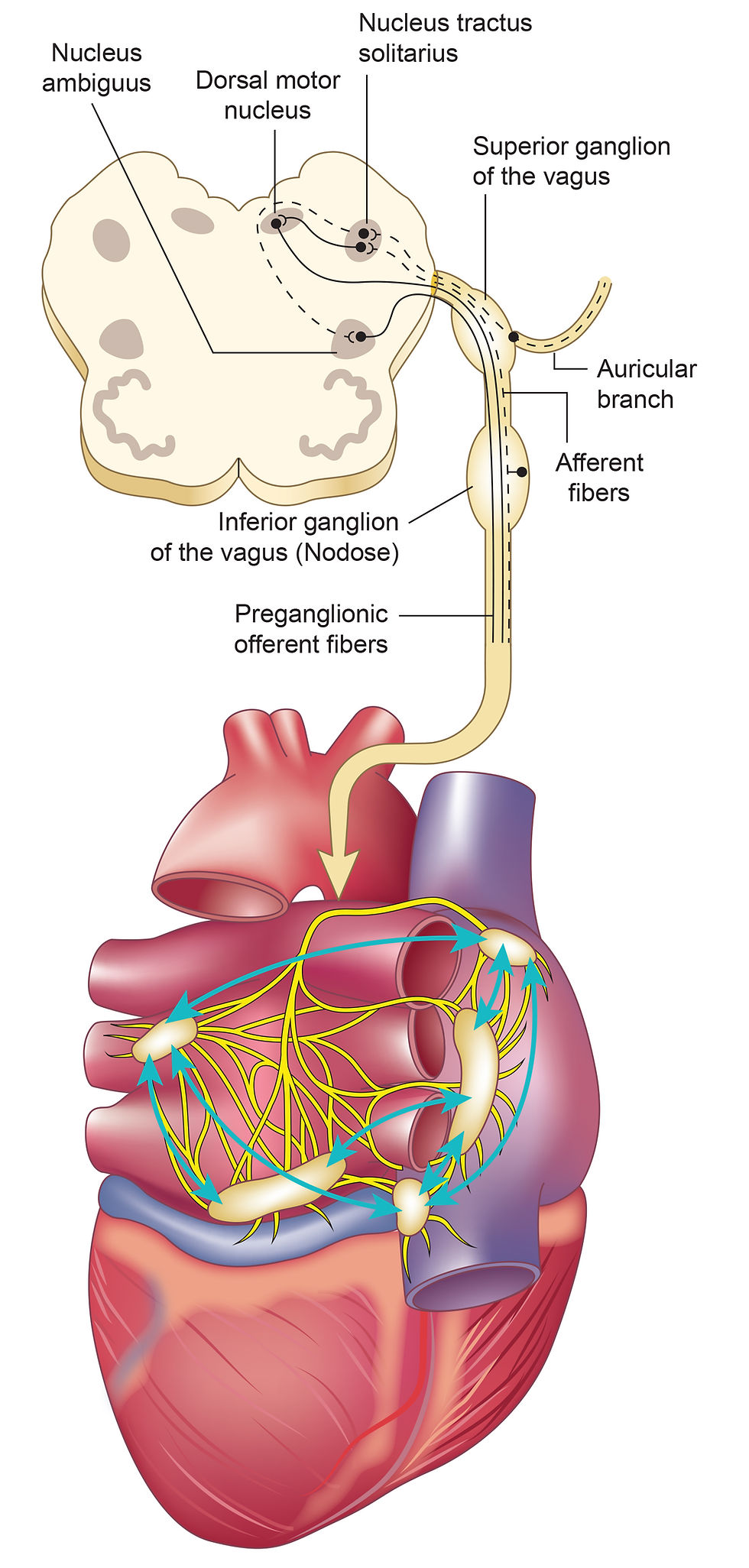

In accessible terms, it is the heart's natural breathing-linked oscillations. Importantly, RSA is mediated by vagal cardioinhibitory pathways, meaning fibers of the vagus nerve that can slow the heart.

The vagus nerve is a major parasympathetic conduit connecting the brainstem to visceral organs.

In Porges' framing, RSA is not just a pretty rhythm. It becomes a practical, noninvasive index of specific neural regulation. That matters because psychophysiology can then test hypotheses about regulation, resilience, and vulnerability using a metric with clearer neurophysiological grounding.

This is one of Porges' enduring contributions: he repeatedly turns "interesting variability" into "interpretable variability," and then uses that interpretability to connect basic mechanisms with clinical and behavioral questions.

The Polyvagal Turn: From Arousal to Organized Hierarchy

Porges describes a key shift in the field's earlier decades. Arousal theory treated activation as a single dimension from low to high, often assuming that measures like heart rate reflected sympathetic "activation" and that physiology might parallel psychological states in a near one-to-one way. He names this strategy psychophysiological parallelism, the assumption that each mental process should have a unique physiological signature if we measure the right channel.

Polyvagal Theory is presented as a demarcation from that parallelism, emphasizing integration and hierarchy in the nervous system rather than simple correspondence. In a hierarchical model, foundational survival circuits in the brainstem shape whether higher functions, including social engagement and flexible cognition, can come online.

Porges locates the public debut of this framework in his 1994 presidential address to the Society for Psychophysiological Research (SPR), later published, and describes it as an attempt to archive principles from decades of HRV and autonomic research while challenging psychophysiology to rethink autonomic reactivity.

The heart of the theory is that autonomic state is regulated by three neural circuits (ventral vagal, sympathetic, and dorsal vagal) organized in a phylogenetically and developmentally ordered hierarchy.

The vagus itself includes distinct efferent pathways, ventral and dorsal, arising from different brainstem regions, with the ventral pathway (linked to the nucleus ambiguus) providing myelinated cardioinhibitory influences in mammals. Myelinated fibers are insulated nerve fibers that conduct signals rapidly, which gives this pathway speed and precision.

The concept of neuroception, the nervous system's detection of safety or threat without conscious awareness, extends the theory into everyday experience: cues of danger can reflexively shift autonomic state toward mobilization or shutdown, while cues of safety support homeostatic regulation and social engagement.

The Vagal Brake: A Practical Metaphor with Real Physiology

One of Porges' most influential explanatory tools is the vagal brake. The idea is simple and elegant. The heart has an intrinsic rhythm, and in young healthy adults this intrinsic rate is about 90 beats per minute. Baseline heart rate is typically slower because the vagus provides chronic cardioinhibitory input to the heart's pacemaker, the sinoatrial node.

The "brake" metaphor captures how quickly this vagal influence can be engaged or released. If vagal influence withdraws, heart rate can rise rapidly even without an increase in sympathetic excitation.

In this framing, RSA amplitude reflects the strength of that brake and can index "homeostatic reserve," meaning how much regulatory flexibility the autonomic nervous system has available when the environment demands action.

This is Porges at his most generous: he translates specialized neurophysiology into language that clinicians, researchers, and lay readers can all use, without abandoning precision.

A Metric that Moves: Vagal Efficiency

Porges also describes methodological innovations meant to capture autonomic dynamics, not just resting levels. His time-frequency methodology allowed RSA estimation over short epochs, enabling the study of rapid changes and relationships between RSA and heart rate. From this comes vagal efficiency, operationalized as the slope of the regression linking changes in RSA amplitude to changes in heart period.

In plain terms, vagal efficiency asks: when vagal regulation changes, how effectively does the heart's timing respond? This is a deeply Porges-like question because it is mechanistic, quantitative, and clinically suggestive.

Why Porges' HRV Research Continues to Matter

Porges closes with an argument that feels both scientific and humane.

If clinicians lack sensitive metrics of neural regulation, then medicine may miss early dysregulation that precedes organ damage.

He emphasizes the importance of visceral afferents, sensory fibers that carry information from organs back to the brainstem, as part of a dynamic feedback system that supports homeostasis.

He also reminds psychophysiology that HRV was once dismissed as error, either poor control or poor measurement, and that a deeper understanding requires abandoning simplistic stimulus-response assumptions. In place of stimulus-response, he highlights a stimulus-organism-response model, where autonomic state is the organism component that shapes what happens next.

Taken together, his "personal journey" reads like a blueprint for responsible bioscience: observe carefully, quantify honestly, interpret mechanistically, and then use what you learn to design better questions and better interventions. It is a career built not only on ideas, but on the ethical obligation to make ideas measurable and therefore testable.

Glossary

afferent fibers: sensory nerve fibers that carry information from the body's organs toward the central nervous system.

arousal theory: a model that treats activation as a single dimension from low to high, often assuming that higher arousal corresponds to more physiological and behavioral activation.

autonomic nervous system (ANS): the part of the nervous system that regulates organs automatically, including heart, lungs, and gut, through sympathetic and parasympathetic branches.

biofeedback: a method that uses real-time physiological signals to help a person learn to influence physiological regulation.

brainstem: a set of structures at the base of the brain that regulate foundational survival functions and autonomic control.

cardioinhibitory pathways: neural pathways that slow the heart, often referring to vagal (parasympathetic) influences on the sinoatrial node.

cardiotachometer: a device or circuit that converts heart electrical activity into beat-to-beat heart rate output for monitoring.

cross-spectral analysis: a time series method that evaluates how two rhythmic signals relate across frequencies, such as respiration and heart rate variability.

David C. Raskin: a pivotal early mentor who shaped the empirical and quantitative foundations of modern psychophysiology. Raskin was trained at UCLA under Irving Maltzman and became an early leader in bringing rigorous physiological monitoring into psychological research. At Michigan State University he helped establish psychophysiology as an emerging discipline, emphasizing precise measurement of autonomic activity, engineering-minded instrumentation, and experimental designs linking learning, attention, and autonomic control. He guided Porges’ first HRV studies, introduced him to physiological recording technologies such as the Dynograph, and modeled a cautious, data-driven scientific style that strongly influenced Porges’ later methodological innovations and theoretical development.

Dynograph: an early physiological recording device that used ink-writing pens to display signals such as beat-to-beat heart rate and electrodermal activity in real time. It allowed researchers to monitor autonomic responses continuously during experiments and was central to Porges’ initial HRV observations

electrocardiogram (ECG): a recording of the heart's electrical activity used to time heartbeats precisely.

heart period: the time interval between consecutive heartbeats, often measured in milliseconds.

heart rate variability (HRV): variation over time in the interval between heartbeats, reflecting dynamic neural influences on the heart.

hierarchical model: a framework in which the autonomic nervous system is organized in evolutionarily layered levels, with newer neural circuits regulating and inhibiting older ones. In Polyvagal Theory, this hierarchy begins with primitive immobilization circuits, then mobilization circuits, and finally the mammalian social engagement system, each level constraining and shaping the function of the one below it.

homeostasis: the body's ongoing effort to maintain internal stability through dynamic regulation and feedback.

myelinated fibers: nerve fibers insulated by myelin that conduct signals rapidly; in Polyvagal Theory, ventral vagal cardioinhibitory pathways are described as myelinated.

neuroception: the nervous system's detection of safety or threat without conscious awareness, shaping autonomic state shifts.

nucleus ambiguus: a brainstem nucleus identified as the source of myelinated ventral vagal cardioinhibitory pathways to the heart in mammals.

parasympathetic nervous system (PNS): the branch of the ANS that supports restoration and conservation processes, prominently including vagal influences on the heart.

Polyvagal Theory: a theory proposing a hierarchical organization of autonomic regulation, emphasizing distinct vagal pathways and their roles in defense, homeostasis, and social engagement.

psychophysiological parallelism: a research strategy assuming that specific mental processes should have unique physiological signatures that directly correspond across levels.

psychophysiology: an interdisciplinary field studying relationships between psychological processes and physiological measures.

respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA): rhythmic variation in heart rate at the frequency of breathing, mediated by vagal cardioinhibitory pathways.

sinoatrial node: the heart's primary pacemaker whose rhythm is slowed by chronic vagal cardioinhibitory influence.

spectral analysis: a method that decomposes a time series into frequency components to quantify how much variability occurs at different rhythms, including respiration-linked rhythms.

stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) model: a framework in which an organism's internal state, including autonomic state, mediates the link between a stimulus and the response.

sympathetic nervous system (SNS): the branch of the ANS associated with mobilization, including fight-or-flight responses.

sympathovagal balance: the idea that sympathetic and parasympathetic influences can be represented as a balance, often via HRV ratios; Porges notes limited evidence for using some HRV components as direct SNS indices.

time series: data measured sequentially over time, analyzed for patterns such as trends and rhythms.

time-frequency method: an approach that estimates how rhythmic components change over time, enabling short-epoch estimates of rhythms like RSA.

vagal brake: a functional metaphor for the rapid engagement and disengagement of vagal influences on the heart's pacemaker, supporting flexible shifts in heart rate.

vagal efficiency: a metric defined as the regression slope relating changes in RSA to changes in heart period, indexing how effectively vagal regulation shifts heart timing.

vagal tone: the chronic cardioinhibitory influence of the vagus on the heart, often indexed using RSA amplitude.

vagus nerve: a major parasympathetic nerve connecting brainstem to organs, supporting bidirectional regulation through efferent and afferent fibers.

ventral vagal pathway: a myelinated vagal pathway originating in the nucleus ambiguus that provides rapid cardioinhibitory regulation and supports social engagement-related regulation.

visceral afferents: sensory nerve fibers that carry continuous information from internal organs to the brainstem. They provide the central nervous system with real-time updates on the physiological status of organs such as the heart, lungs, and gut, enabling the autonomic nervous system to regulate homeostasis through feedback processes.

Reference

Porges, S. W. (2022). Heart rate variability: A personal journey. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 47(4), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-022-09559-x

About the Author

Fred Shaffer earned his PhD in Psychology from Oklahoma State University. He earned BCIA certifications in Biofeedback and HRV Biofeedback. Fred is an Allen Fellow and Professor of Psychology at Truman State University, where has has taught for 50 years. He is a Biological Psychologist who consults and lectures in heart rate variability biofeedback, Physiological Psychology, and Psychopharmacology. Fred helped to edit Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd and 4th eds.) and helped to maintain BCIA's certification programs.

Support Our Friends

Comments