Inter-Organ Communication: A Paradigm Shift

- Fred Shaffer

- Feb 10

- 20 min read

Updated: Feb 16

This post summarizes Claire Ainsworth's (2026) game-changing NewScientist article, "The secret signals our organs send to repair tissues and slow ageing."

Inter-Organ Communication: "It's All Connected"

The human body has long been understood to coordinate its functions through two principal communication channels: the nervous system and the endocrine system (the hormonal system). However, research emerging from the new field of inter-organ communication is fundamentally revising this picture.

Scientists are now discovering that organs engage in a rich, multidirectional web of “crosstalk” that extends far beyond what nerves and hormones alone can account for.

The signals involved include specialized proteins, metabolites, RNA fragments, and, most surprisingly, tiny membrane-bound packages called extracellular vesicles (EVs) that physically transport molecular cargo from one organ to another.

This field builds on the older physiological idea that organ systems are interconnected, but what is extraordinary about recent discoveries is the sheer scope and complexity of these conversations.

Rather than a simple top-down command structure originating in the brain or a handful of endocrine glands, virtually every organ and tissue appears to participate as both sender and receiver in an ongoing, body-wide dialogue. These communication networks influence everything from bone density and fat metabolism to brain function, immune regulation, and the pace of biological ageing itself.

By understanding and eventually tapping into these communication networks, researchers believe it may be possible to develop radical new therapies for conditions ranging from osteoporosis and obesity to neurodegenerative diseases and the multimorbidity that characterizes old age.

The post profiles several key researchers and highlights discoveries spanning multiple organ systems, each contributing pieces to a picture of the body as an astonishingly coordinated collective.

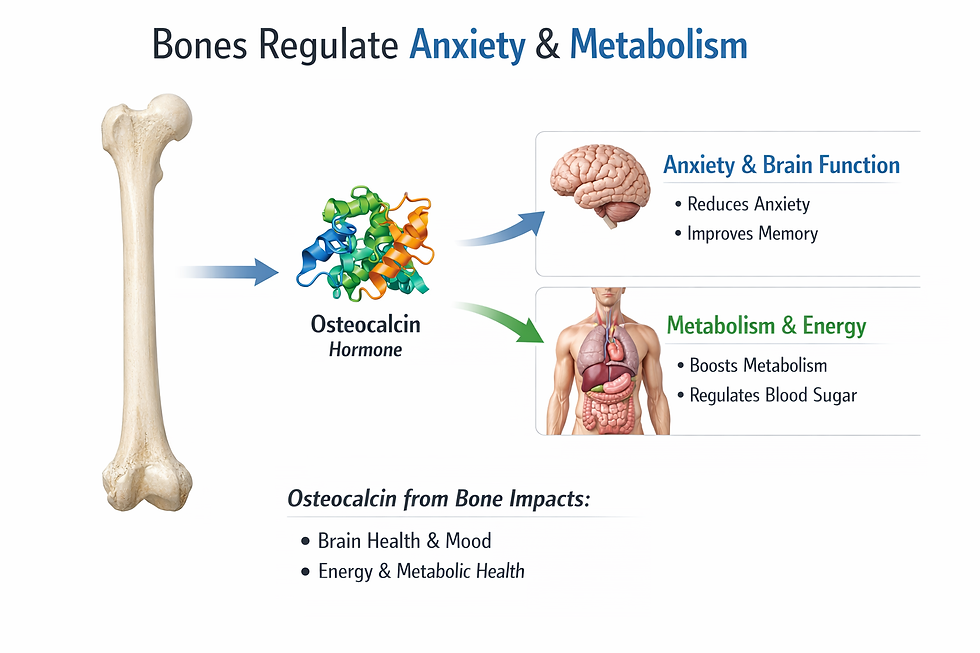

Bone and the Skeletal System: Bone as a Signaling Organ

One of the biggest surprises to emerge from inter-organ communication research is the recognition that bone is not merely a passive mechanical scaffold supporting the body. Instead, the skeleton functions as a dynamic endocrine organ that sends signals to a wide array of other tissues and organs.

This reconceptualization of bone began gaining traction in the mid-1990s, when researchers first discovered that certain tissues previously considered inert were actually producing and releasing signaling molecules that could influence distant organs.

Bone produces the hormone osteocalcin, which has been found to exert effects on multiple organ systems. Osteocalcin influences metabolism and fertility in ways that were entirely unsuspected until relatively recently. Perhaps most remarkably, osteocalcin signals even reach the brain, where research has shown that it reduces anxiety.

This means that the skeleton, long seen as structurally important but biochemically passive, is in fact participating in the regulation of mood and cognitive function through chemical messengers it actively secretes into the bloodstream.

Why Bone Communicates So Extensively

The skeleton’s involvement in so many inter-organ conversations is attributed to the enormous energetic cost of maintaining and repairing bone tissue. The body must continuously repair tiny fractures caused by everyday mechanical stress, and this constant turnover requires substantial metabolic resources.

According to Gerard Karsenty at Columbia University in New York, this is precisely why bone has evolved such a prominent role as a signaling hub. Because bone is so metabolically demanding, it needs to maintain active communication with other organs that supply it with energy and nutrients, and in return it sends out signals that coordinate broader metabolic processes.

Interactions Between Bone and Fat

A key example of bone’s inter-organ communication involves its relationship with adipose tissue (fat tissue). Fat communicates with bone through the hormone leptin. In 2002, researchers discovered that fat tissue, via leptin signaling, functions as a major regulator of bone mass.

This fat-to-bone signaling pathway helps explain why changes in body composition, such as significant weight loss or gain, can have profound effects on skeletal health.

The bidirectional nature of this relationship means that interventions targeting one system inevitably affect the other, a consideration that has important implications for treating conditions like osteoporosis, particularly in populations with metabolic disorders or obesity.

Therapeutic Implications: Osteoporosis Treatment

The discovery of inter-organ signaling pathways involving bone has opened up new avenues for treating skeletal diseases. A 2018 study demonstrated that certain signals involved in bone-organ crosstalk can be blocked, or “jammed,” using existing blood-pressure medications.

This finding is significant because it suggests that drugs already approved for other purposes might be repurposed to treat osteoporosis by interrupting harmful signaling patterns between organs.

The broader implication is that osteoporosis may not simply be a disease of bone itself, but rather a breakdown in the communication networks that maintain skeletal health, and that restoring or modulating those networks could be a more effective therapeutic strategy than targeting bone in isolation.

Fat and Adipose Tissue: Fat as a Communicating Organ

Fat tissue, once regarded as little more than an inert energy storage depot, is now understood to be a highly active endocrine organ. It secretes a variety of signaling molecules, collectively known as adipokines, that influence organs throughout the body. The hormone leptin, produced by fat cells, is one of the best-characterized adipokines and plays a key role in regulating bone mass, appetite, and energy balance.

Obesity and Extracellular Vesicle Signaling

Research has revealed that obesity exerts many of its harmful systemic effects through extracellular vesicles released by adipose tissue. These EVs carry molecular cargo, including proteins, lipids, and small RNA molecules, that can alter the behavior of cells in distant organs.

Obesity-related EVs have been implicated as a communication pathway through which excess fat tissue contributes to metabolic dysfunction elsewhere in the body.

One particularly concerning finding is that EVs released from fat tissue in obese individuals are emerging as an important factor in the development of liver disease caused by metabolic dysfunction.

Previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), this condition is now understood to involve active signaling from adipose tissue to the liver via EVs, which can reprogram liver cells and promote inflammation, fibrosis, and other pathological changes.

This underscores the idea that obesity is not merely a local problem of excess fat storage but a systemic communication disorder with far-reaching consequences for multiple organ systems.

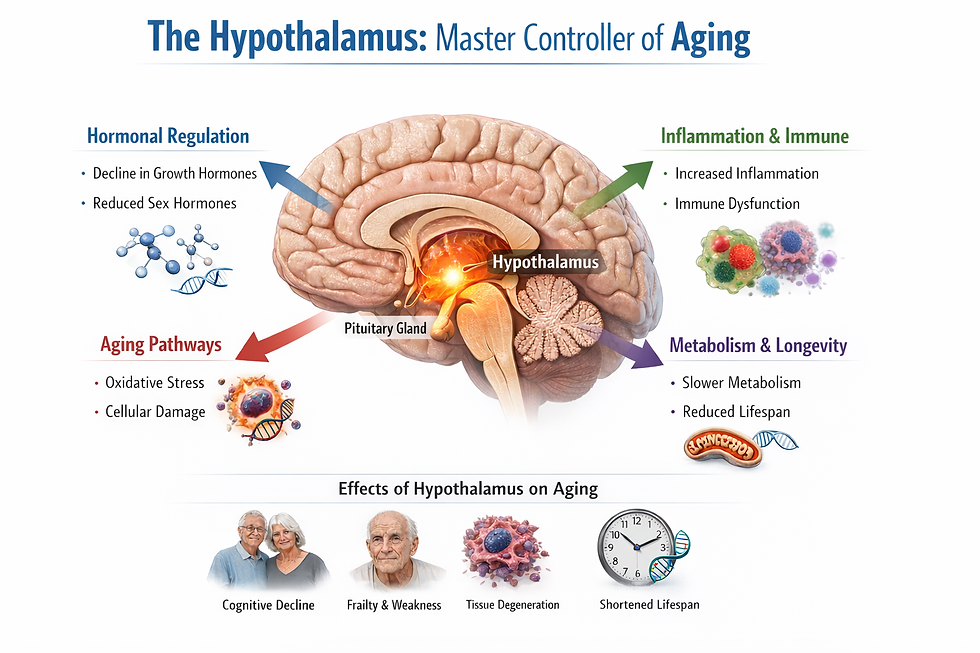

Brain and the Hypothalamus: The Hypothalamus as a Longevity Controller

The brain, particularly the hypothalamus, occupies a central position in inter-organ communication networks related to ageing.

Shin-ichiro Imai and his colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, have been working to understand ageing as a multi-layered phenomenon that spans from the molecular level through cells, tissues, and organs.

Imai’s perspective emphasizes the need to understand the whole system—from the molecular layer through the cellular layer, tissue layer, and organ layer—in order to grasp how ageing unfolds.

In 2024, Imai’s group published a landmark finding showing that a particular subset of hypothalamic neurons plays a critical role in controlling lifespan.

When they stimulated these specific neurons in old mice, the mice lived longer than control mice that did not receive this stimulation. This was described as the first demonstration in mammals that manipulation of specific neurons can genuinely delay ageing and extend lifespan.

The finding positions the hypothalamus not merely as a regulator of homeostasis, as has long been understood, but as a master controller of the ageing process itself, one that integrates signals from multiple organ systems to coordinate biological decline or maintenance.

Multi-Organ Communication Management

The hypothalamus receives signals from multiple organs, including skeletal muscle and the small intestine, among others. In unpublished work referenced in the article, researchers have been mapping these incoming communication pathways to understand how the brain integrates information from diverse organ sources.

Each of these communication pathways operates independently but synergistically to maintain the overall system’s robustness, according to Imai. He envisions a therapeutic approach he calls multi-organ communication management, which would involve simultaneous interventions designed to strengthen each of the brain-organ conversations that deteriorate with age.

Rather than targeting a single pathway or organ, this approach would aim to restore the entire communication network, potentially slowing or reversing the coordinated decline that characterizes ageing.

Heart and Cardiovascular System: Cardiac Extracellular Vesicles and Organ Damage

The heart is both a sender and receiver in inter-organ communication networks, and its signaling behavior has significant implications for understanding how cardiovascular disease affects other organs.

In a 2022 study, Saumya Das at Harvard Medical School and his colleagues demonstrated that when the heart is damaged, it releases extracellular vesicles that travel through the bloodstream to the kidneys. These EVs carry harmful microRNAs, small RNA molecules that can alter gene expression in recipient cells, and they cause damage to kidney tissue upon arrival.

This finding is clinically important because it helps explain a well-known but poorly understood phenomenon: patients with heart failure frequently develop kidney disease, a condition sometimes referred to as cardiorenal syndrome.

The discovery that damaged hearts actively send harmful molecular signals to the kidneys via EVs suggests that kidney damage in heart failure patients is not merely a secondary consequence of impaired circulation but rather a direct result of pathological inter-organ communication.

This opens the door to potential therapies that could intercept these harmful EVs or block their damaging cargo, potentially protecting the kidneys in patients with cardiac disease.

Liver Metabolic Liver Disease and Inter-Organ Signaling

The liver is a major recipient of inter-organ signals, and its health is increasingly understood to depend on communication networks involving other organs, particularly adipose tissue.

As noted above, EVs released by fat tissue in obese individuals are emerging as an important factor in liver disease caused by metabolic dysfunction. These EVs can deliver molecular cargo that reprograms liver cells, promoting inflammatory responses and fibrotic changes that drive the progression of metabolic liver disease.

This reframing of liver disease as a condition influenced by distant organ signaling, rather than solely by local factors like alcohol consumption or viral infection, represents a significant shift in how clinicians and researchers think about hepatic pathology.

It suggests that effective treatment of certain forms of liver disease may require addressing the upstream sources of harmful signals, particularly in adipose tissue, rather than focusing exclusively on the liver itself.

Kidneys: Vulnerability to Inter-Organ Signaling

The kidneys serve as a critical example of how inter-organ communication can contribute to organ damage and disease. As described in the work by Saumya Das, the kidneys are targets of harmful EVs released by the damaged heart. These EVs deliver microRNAs that cause damage to kidney tissue, contributing to the development of renal dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease.

The kidney’s vulnerability to harmful inter-organ signaling highlights a broader principle: organs do not fail in isolation. When one organ is diseased or damaged, it can actively undermine the health of other organs through pathological signaling, creating cascading failures across multiple systems.

Conversely, damaged kidneys release molecules that are toxic to the heart and which promote heart failure.

Understanding these inter-organ damage pathways is essential for developing comprehensive treatment strategies that address not just the primary diseased organ but also the secondary organs at risk from harmful crosstalk.

Skeletal Muscle: Muscle as a Communicating Tissue

Skeletal muscle is now recognized as an organ that actively participates in inter-organ communication.

Muscles produce and release signaling molecules called myokines when they contract, and these myokines act on many other tissues, including the brain and liver. This discovery helps explain the well-documented systemic health benefits of exercise, which extend far beyond the musculoskeletal system to include improvements in cognitive function, metabolic regulation, and immune function.

Skeletal muscle also communicates with the hypothalamus, contributing to the brain’s ability to monitor and coordinate whole-body metabolism. The muscle-to-brain signaling pathway is one of the multiple independent but synergistic communication channels that Imai’s group has been studying in the context of ageing and longevity.

Muscle Wasting and Chronic Disease

Inter-organ communication research is beginning to yield therapeutic insights for conditions involving muscle wasting. For instance, researchers are investigating how metabolites associated with chronic kidney disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can reprogram immune cells, which then promote muscle wasting.

This represents a clear example of inter-organ crosstalk gone wrong: metabolic signals from diseased kidneys or lungs alter immune cell behavior, and these reprogrammed immune cells then attack and degrade muscle tissue. Understanding this signaling chain could lead to interventions that break the cycle and preserve muscle mass in patients with chronic diseases.

Small Intestine and Gut: Gut-to-Brain Communication

The small intestine is another organ that communicates with the hypothalamus, contributing to the brain’s integration of signals from across the body. While the article does not detail the specific molecules involved in gut-to-brain signaling, it notes that this pathway is among those being actively studied by Imai’s group.

The gut-brain axis has been a subject of intense research interest in recent years, and its inclusion in the inter-organ communication framework adds another layer to our understanding of how digestive health influences systemic well-being, including ageing.

Immune System and Senescent Cells: Senescent Cells and Ageing

A key factor in biological ageing is the accumulation of senescent cells, which are cells that have stopped dividing but remain metabolically active.

Rather than quietly retiring, senescent cells actively promote inflammation and tissue damage through a collection of secreted factors known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

Among the components of the SASP are extracellular vesicles, and these EVs play a pivotal role in spreading the effects of cellular senescence throughout the body.

Senescent cells release EVs that function, as the article describes, like sparks from a fire, spreading inflammation and damage from one tissue to another.

This EV-mediated spread of senescence signals probably contributes to the “multimorbidity of the elderly,” the clinical observation that older people typically suffer from several chronic conditions simultaneously rather than just one.

The interconnected nature of these conditions may reflect the body-wide dissemination of harmful signals via senescent cell-derived EVs.

Immune Evasion

Recent research has also revealed that EVs can undermine the immune surveillance response against diseased or dysfunctional cells.

This finding suggests that senescent cells and potentially cancer cells may use EVs as a mechanism for evading immune detection, allowing them to persist and continue causing damage.

Understanding how EVs interact with the immune system could lead to strategies for enhancing the body’s ability to clear senescent cells and fight cancer.

Extracellular Vesicles: The Body’s Molecular Postal Service

Overview of EVs

One of the most exciting discoveries in inter-organ communication is the recognition that many signaling molecules are transported between organs not as free-floating molecules in the blood but packaged inside extracellular vesicles.

EVs are membrane-bound packages that range enormously in size and cargo. At one end of the spectrum are large vesicles bearing intact mitochondria (the cell’s energy-producing organelles). At the other end are tiny exosomes, typically 30 to 150 nanometers in diameter, that carry fragments of RNA, proteins, and lipids.

Diversity of EV Types

The diversity of EV types continues to expand as researchers develop better analytical tools. New varieties are constantly being discovered.

For example, researchers recently identified particularly massive EVs dubbed with new terminology to distinguish them from previously known types. There are also non-membrane-enclosed particles that carry signaling cargo, as well as oncosomes, which are EVs produced specifically by cancer cells.

All of these are emerging as important players in health and disease.

EVs in Disease

EVs have been implicated in a growing list of pathological processes. In cardiovascular disease, damaged hearts release EVs carrying harmful microRNAs that damage the kidneys. In obesity, fat-derived EVs contribute to metabolic liver disease.

Recent studies also show that EVs are implicated in neurodegenerative conditions, suggesting that the progressive neuronal loss seen in diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s may be influenced by pathological EV signaling from other organs or from within the brain itself.

EVs and Ageing

The role of EVs in ageing is attracting particular attention. Senescent cells use EVs to spread inflammatory and damaging signals throughout the body, contributing to the multimorbidity characteristic of old age.

Understanding how to intercept, redirect, or modify these EV-based signals could open up entirely new approaches to slowing biological ageing and extending healthspan.

Antler Regeneration as a Model System

The article opens and closes with the story of biologist Chunyi Li, who has studied deer in northeast China for four decades. Li, working at Changchun Sci-Tech University in Jilin, noticed something remarkable: the annual regrowth of deer antlers, one of the most dramatic examples of organ regeneration in mammals, appeared to trigger a wider regenerative response throughout the animal’s body, including improved wound healing and tissue repair in areas far from the antlers themselves.

Li’s observation was confirmed in research published in 2025, when he and his colleagues demonstrated that the growing antlers release signals that stimulate regeneration in other parts of the deer’s body. The antler regeneration process involves both local conversations (signaling within and around the antler itself) and long-distance communication through the bloodstream, producing whole-body regenerative effects that repair tissues almost scar-free.

Parallels with Axolotl Regeneration

Li’s findings parallel discoveries in other regenerating animals. When an axolotl’s leg is amputated, the injury triggers a body-wide reaction. Cells at the injury site revert to a more embryonic-like state, and remarkably, cells in the opposite, uninjured limb enter an “alert” state that allows them to respond to any subsequent injury more rapidly.

This alert state is triggered by a signal carried in the blood, demonstrating that regeneration is not solely a local phenomenon but involves coordinated, systemic communication across the entire organism.

Toward Human Applications

Li and his team are now working on developing a formula based on the regenerative signals identified in deer antlers, with the goal of testing it in humans. If successful, this could represent a major advance in regenerative medicine, leveraging the principles of inter-organ communication to enhance the human body’s capacity for tissue repair.

The Spatial Dimension: Why So Many Languages?

Communication Specificity

Organs do not rely on a single mode of communication. Instead, they employ a diverse array of signaling systems, including hormones, neurotransmitters, myokines, adipokines, metabolites, EVs, and direct nerve connections.

The article raises the question of why so many different “languages” are needed, and offers several possible explanations.

One possibility is that the physical location of the communication matters. Different tissues may contain receptors for specific substances, and the spatial arrangement or geometry of these receptors can alter how they function.

This spatial specificity means that the same signaling molecule may produce different effects depending on where in the body it is received.

Irene Miguel-Aliaga suggests that this spatial specificity is going to prove very important, adding a layer of information and nuance that is only beginning to be appreciated.

Versatility and Precision

Another reason for the multiplicity of communication systems may be that it offers greater versatility in targeting particular messages to particular tissues. Different types of EVs, for instance, appear to have different tropisms, meaning they tend to be taken up preferentially by certain cell types or organs.

This selectivity allows the body to send tailored messages to specific targets without affecting bystander tissues, an essential capability for maintaining the complex coordination required to run a multicellular organism.

Implications for the Complexity of Coordination

The existence of so many inter-organ languages highlights the staggering complexity of coordinating a collective of trillions of cells organized into dozens of distinct organ systems.

While we do not yet fully understand why so many communication systems are needed, their existence suggests that the body’s internal communication network is far richer and more sophisticated than previously appreciated.

This complexity also means that disruptions in inter-organ communication, whether caused by disease, injury, or ageing, can have cascading effects that are difficult to predict from studying any single organ in isolation.

Therapeutic Horizons: From Discovery to Treatment

The challenge ahead for the field of inter-organ communication is translating these basic science discoveries into new clinical therapies. Several promising directions are emerging. The repurposing of blood-pressure drugs to block bone-related signaling could lead to new osteoporosis treatments.

Imai’s concept of multi-organ communication management envisions comprehensive interventions that simultaneously strengthen multiple brain-organ communication pathways to slow ageing.

Research into muscle wasting driven by inter-organ metabolite signaling in chronic kidney and pulmonary disease is already suggesting new therapeutic targets.

Regenerative Medicine

Perhaps most ambitiously, the work on deer antler regeneration and axolotl limb regeneration suggests that restoring good communication—at local, organ-wide, and body-wide levels—could help us understand more about regeneration and perhaps eventually enhance the human body’s own regenerative capacities.

Li’s team is actively developing a formula based on deer antler regeneration signals for testing in humans, which could represent a transformative advance if it proves effective.

GLP-1 Drugs and Broader Applications

GLP-1 drugs, such as Ozempic and Wegovy, appear to have unexpectedly wide-ranging effects across multiple organ systems. The broad efficacy of these drugs may be partly explained by their influence on inter-organ communication networks, further underscoring the clinical relevance of this emerging field.

Conclusion

The emerging picture from inter-organ communication research is one of the body as a deeply interconnected collective in which every organ participates in ongoing conversations that maintain health, coordinate responses to injury, and regulate the pace of ageing.

Understanding these conversations in their full complexity—from the molecular details of EV cargo to the systemic architecture of brain-organ signaling networks—represents one of the most exciting frontiers in biomedical science.

As Chunyi Li’s four-decade journey from observing deer antlers to discovering whole-body regeneration signals illustrates, patient observation and cross-species insight can reveal principles of profound medical significance. Our organs, it turns out, have been carrying on rich conversations all along. We are only now learning to listen.

Key Takeaways

Every organ is both a sender and a receiver in a body-wide signaling network that uses hormones, metabolites, myokines, adipokines, extracellular vesicles, and nerve signals—not just the nervous and endocrine systems.

Extracellular vesicles are a recently discovered communication channel that can spread both healing and harm, carrying microRNAs that alter gene expression in distant organs.

Bone, fat, and muscle are now recognized as endocrine organs whose secretions influence the brain, metabolism, and aging—reframing exercise and body composition as communication variables, not just fitness metrics.

Organs do not fail in isolation: damaged hearts send pathological vesicles to kidneys, obese fat tissue drives liver fibrosis, and senescent cells broadcast inflammation body-wide, which helps explain why chronic diseases cluster.

Training one physiological system through biofeedback may improve the entire network because inter-organ signals are synergistic—strengthening one conversation (e.g., heart-brain via HRV) can cascade benefits to the gut, immune system, and metabolic function.

Glossary

adipokines: signaling molecules secreted by adipose (fat) tissue that influence the function of distant organs. Leptin is one of the best-characterized adipokines.

adipose tissue: the body’s fat tissue, now recognized as an active endocrine organ that produces hormones and signaling molecules affecting bone, liver, brain, and other organs.

axolotl: a neotenic salamander (Ambystoma mexicanum) capable of extensive regeneration, including whole limbs. Used as a model organism for studying body-wide regenerative responses to injury.

cardiorenal syndrome: a clinical condition in which dysfunction of the heart leads to damage in the kidneys (or vice versa), now understood to involve pathological signaling via extracellular vesicles carrying harmful microRNAs.

chronic kidney disease: a progressive condition in which the kidneys gradually lose function over time. Metabolites associated with this disease can reprogram immune cells, contributing to muscle wasting through inter-organ crosstalk.

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a group of lung diseases that block airflow and make breathing difficult. Like chronic kidney disease, metabolites from COPD can alter immune cell behavior, leading to muscle wasting.

endocrine glands: organs or tissues that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream to regulate distant target organs.

endocrine organ: an organ that produces and secretes hormones into the bloodstream. Bone, fat, and muscle are now recognized as endocrine organs in addition to traditional glands such as the thyroid and adrenals.

endocrine system: the collection of glands and organs that produce hormones to regulate metabolism, growth, reproduction, and other body functions.

exosomes: small extracellular vesicles, typically 30 to 150 nanometers in diameter, that carry fragments of RNA, proteins, and lipids between cells and are involved in inter-organ communication.

extracellular vesicles (EVs): membrane-bound packages of molecular cargo (proteins, RNA, lipids, and sometimes mitochondria) released by cells and transported through the bloodstream to influence distant organs.

fibrosis: the formation of excess fibrous connective tissue in an organ or tissue, typically as part of a reparative or reactive process. In the context of liver disease, fibrosis is driven in part by EVs from adipose tissue.

gene expression: the process by which information from a gene is used to synthesize functional products such as proteins. MicroRNAs transported by EVs can alter gene expression in recipient cells.

GLP-1 drugs: a class of medications (including semaglutide, marketed as Ozempic and Wegovy) that mimic glucagon-like peptide-1 and have wide-ranging effects across multiple organ systems, possibly through inter-organ communication pathways.

gut-brain axis: the bidirectional communication network between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain, now recognized as part of the broader inter-organ communication framework.

healthspan: the period of life during which a person is generally in good health, free from serious chronic illness or disability. Distinguished from lifespan, which measures total years lived.

homeostasis: the maintenance of stable internal physiological conditions (temperature, pH, blood glucose, etc.) by the body’s regulatory systems. The hypothalamus plays a central role in homeostatic regulation.

hypothalamic neurons: nerve cells located in the hypothalamus that participate in regulating metabolism, ageing, and inter-organ communication. Stimulation of a specific subset of these neurons in mice extended lifespan.

hypothalamus: a small region at the base of the brain that serves as a central hub for integrating inter-organ signals and regulating homeostasis, metabolism, and, as recent research shows, the pace of ageing.

immune surveillance: the process by which the immune system monitors the body for abnormal cells, including senescent cells and cancer cells. EVs released by dysfunctional cells may undermine this surveillance.

inter-organ communication: the exchange of signals between different organs and tissues in the body, mediated by hormones, metabolites, myokines, adipokines, extracellular vesicles, nerves, and other pathways.

leptin: a hormone produced by adipose tissue that regulates appetite, energy balance, and bone mass. Leptin’s role as a regulator of bone mass was established in 2002.

metabolic dysfunction: impairment of the body’s normal metabolic processes, often associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and related conditions. EVs from adipose tissue contribute to metabolic dysfunction in distant organs.

metabolic liver disease: liver disease caused by metabolic dysfunction, previously termed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Increasingly understood to involve inter-organ signaling from adipose tissue via EVs.

metabolites: small molecules produced during metabolism that serve as substrates, intermediates, or products of biochemical reactions. Some metabolites function as inter-organ signals.

microRNAs: small non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression by binding to messenger RNA. MicroRNAs carried by extracellular vesicles can alter cell behavior in distant organs.

mitochondria: organelles within cells that produce energy through oxidative phosphorylation. Large extracellular vesicles can transport intact mitochondria between cells as part of inter-organ communication.

multi-organ communication management: a therapeutic concept proposed by Shin-ichiro Imai involving simultaneous interventions to strengthen multiple brain-organ communication pathways in order to slow ageing.

multimorbidity: the co-occurrence of two or more chronic diseases in the same individual, particularly common in the elderly. EV-mediated spread of senescence signals may contribute to multimorbidity.

muscle wasting: progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, often associated with chronic diseases such as kidney disease and COPD. Inter-organ signaling involving reprogrammed immune cells contributes to this process.

myokines: signaling molecules produced and released by skeletal muscle during contraction that act on distant organs, including the brain and liver, and help explain the systemic health benefits of exercise.

nervous system: the network of nerves and neurons that transmits signals between the brain and the rest of the body. One of the two traditionally recognized channels of inter-organ communication (alongside the endocrine system).

neurodegenerative diseases: progressive conditions involving the loss of structure or function of neurons, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. EVs are implicated in the pathogenesis of these conditions.

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a now outdated term for liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction rather than alcohol use. Currently referred to as metabolic liver disease.

oncosomes: extracellular vesicles produced by cancer cells that carry molecular cargo capable of influencing surrounding tissues and potentially facilitating tumor growth and metastasis.

osteocalcin: a hormone produced by bone that influences metabolism, fertility, and brain function (including anxiety reduction). Its discovery helped establish bone as an endocrine organ.

osteoporosis: a condition characterized by reduced bone density and increased fracture risk. Inter-organ communication research suggests that osteoporosis may result from disrupted signaling networks, not just bone pathology alone.

regeneration: the biological process by which organisms regrow lost or damaged tissues or organs. In deer and axolotls, regeneration involves coordinated inter-organ signaling that produces body-wide effects.

regenerative medicine: a branch of medicine focused on repairing or replacing damaged tissues and organs, increasingly informed by inter-organ communication research and principles observed in regenerating animals.

senescence: a state in which cells permanently stop dividing but remain metabolically active, releasing pro-inflammatory factors and EVs that contribute to tissue damage and ageing.

senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): the collection of pro-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles released by senescent cells that promote inflammation and damage in surrounding tissues.

senescent cells: cells that have irreversibly stopped dividing but continue to secrete inflammatory and damaging molecules (the SASP), contributing to tissue deterioration and age-related disease.

signaling molecules: chemical substances (hormones, cytokines, myokines, adipokines, metabolites, etc.) that transmit information between cells and organs to coordinate physiological processes.

spatial specificity: the principle that the physical location at which a signaling molecule acts can determine its biological effect. Receptor geometry and tissue-specific receptor expression contribute to spatial specificity.

tropisms: in the context of extracellular vesicles, the tendency of different EV types to be preferentially taken up by specific cell types or organs, allowing targeted delivery of molecular messages.

References

Chatterjee, E., Rodosthenous, R. S., Kujala, V., Gokulnath, P., Spanos, M., Lehmann, H. I., Pereira de Oliveira, G., Shi, M., Miller-Fleming, T. W., Li, G., Ghiran, I. C., Karalis, K., Lindenfeld, J., Mosley, J. D., Lau, E. S., Ho, J. E., Sheng, Q., Shah, R., & Das, S. (2022). Circulating extracellular vesicles in human cardiorenal syndrome promote renal injury in a kidney-on-chip system. JCI Insight, 7(19), e165172. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.165172

Lago-Baameiro, N., Camino, T., Vazquez-Durán, A., Sueiro, A., Couto, I., Santos, F., Baltar, J., Falcón-Pérez, J. M., & Pardo, M. (2025). Intra and inter-organ communication through extracellular vesicles in obesity: Functional role of obesesomes and steatosomes. Journal of Translational Medicine, 23(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-06024-7

Moser, S. C., & van der Eerden, B. C. J. (2019). Osteocalcin—A versatile bone-derived hormone. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 9, 794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00794

Shan, C., Ghosh, A., Bhattacharjee, S., & Chen, G. (2019). Roles for osteocalcin in brain signalling: Implications in cognition- and motor-related disorders. Molecular Neurobiology, 56(8), 5507–5519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-019-1465-x

Takeda, S., Elefteriou, F., Levasseur, R., Liu, X., Zhao, L., Parker, K. L., Armstrong, D., Ducy, P., & Karsenty, G. (2002). Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell, 111(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01049-8

Tokizane, K., Brace, C. S., & Imai, S. (2024). DMHPpp1r17 neurons regulate aging and lifespan in mice through hypothalamic-adipose inter-tissue communication. Cell Metabolism, 36(2), 377–392.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.011

Tokizane, K., & Imai, S. (2024). Inter-organ communication is a critical machinery to regulate metabolism and aging. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 36(8), 756–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2024.11.013

Zhu, H., Guo, D., Li, K., Pedersen, H. K., Karlsson, B. S. A., Zeng, N., Shen, B., & Zhang, N. (2022). Extracellular vesicles in pathogenesis and treatment of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 909516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.909516

About the Author

Fred Shaffer earned his PhD in Psychology from Oklahoma State University. He earned BCIA certifications in Biofeedback and HRV Biofeedback. Fred is an Allen Fellow and Professor of Psychology at Truman State University, where has has taught for 50 years. He is a Biological Psychologist who consults and lectures in heart rate variability biofeedback, Physiological Psychology, and Psychopharmacology. Fred helped to edit Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd and 4th eds.) and helped to maintain BCIA's certification programs.

Support Our Friends

Comments