Neurofeedback Shows Promise in Treating Traumatic Brain Injury

- BioSource Faculty

- Jun 8, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 31, 2023

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) results when an external force produces intracranial injury through acceleration or direct impact. NF treats mild TBI (mTBI) symptoms, including memory, attention, and decision-making deficits.

TBI can result from so-called “open” injuries when something penetrates the skull, such as a bullet, and “closed” injuries occurring during acceleration-deceleration injuries. Examples include a motor vehicle collision or when the head and a hard object come into forceful contact, such as during a fall. TBI can also result in diffuse and/or localized damage. Localized damage is very unlikely following mTBI.

Click on our narrator icon to listen to this post.

TBI is an issue that has attracted increasing attention in recent years. The 2015 film Concussion exposed the denial and active suppression of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) findings reported by Nigerian-born pathologist Bennet Omalu. Concussion focused on American football and the repetitive concussions experienced by many players that Dr. Omalu identified as leading to CTE. Other researchers and clinicians have focused on TBI related to military service, particularly combat, including exposure to blast injury. Peskind and colleagues (2013) reported that approximately 28,000 military service members each year experience TBI, many considered mild but often repetitive. David Brody, MD, defined mTBI as follows: "Traumatic brain injury is damage to the brain's structure and function caused by an acute external physical force. What is considered 'mild' has varied quite a bit, but a widely used definition of mTBI is loss of consciousness for up to 30 minutes, a change in mental status for up to 24 hours, or posttraumatic amnesia for up to 24 hours. If any of these problems last longer than the specified time, or if intracranial pathology appears on structural imaging of the brain, then the injury is considered moderate or severe. Acute symptoms may appear immediately or a few minutes after the injury." Concussion is another term often used to define the consequences of such an injury and is also considered a mTBI. Measurable cognitive deficits following mTBI are rare after several months and are probably attributable to non-cerebral causes (Belanger et al., 2018). More than 90% of individuals with more than 5 mTBI episodes had a neurologic deficit, while less than 20% of those with a single episode had such a deficit. Helmet-installed technology shows that a single player can experience 900 head impacts per season in high school football (Broglio, 2011) and nearly 1500 impacts in college football (Crisco, 2010).

With the increasing awareness of and attention to mTBI and its consequences, it has become important to identify the brain effects of such events and develop methods to remediate such damage. Most mild injuries do not produce identifiable findings in standard imaging studies such as CT or MRI; diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has also proved inconclusive (Rosenfeld, 2013). Most mTBIs are diagnosed using careful clinical assessment of the injured person and witnesses as soon as possible to the time of injury. Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), a form of MRI, provided additional sensitivity beyond DTI in the neuroimaging of mTBI (e.g., Beauchamp et al., 2013). Neuropsychological tests, questionnaires, and symptom-tracking methods may be helpful 2-3 months after injury if symptoms do not spontaneously resolve.

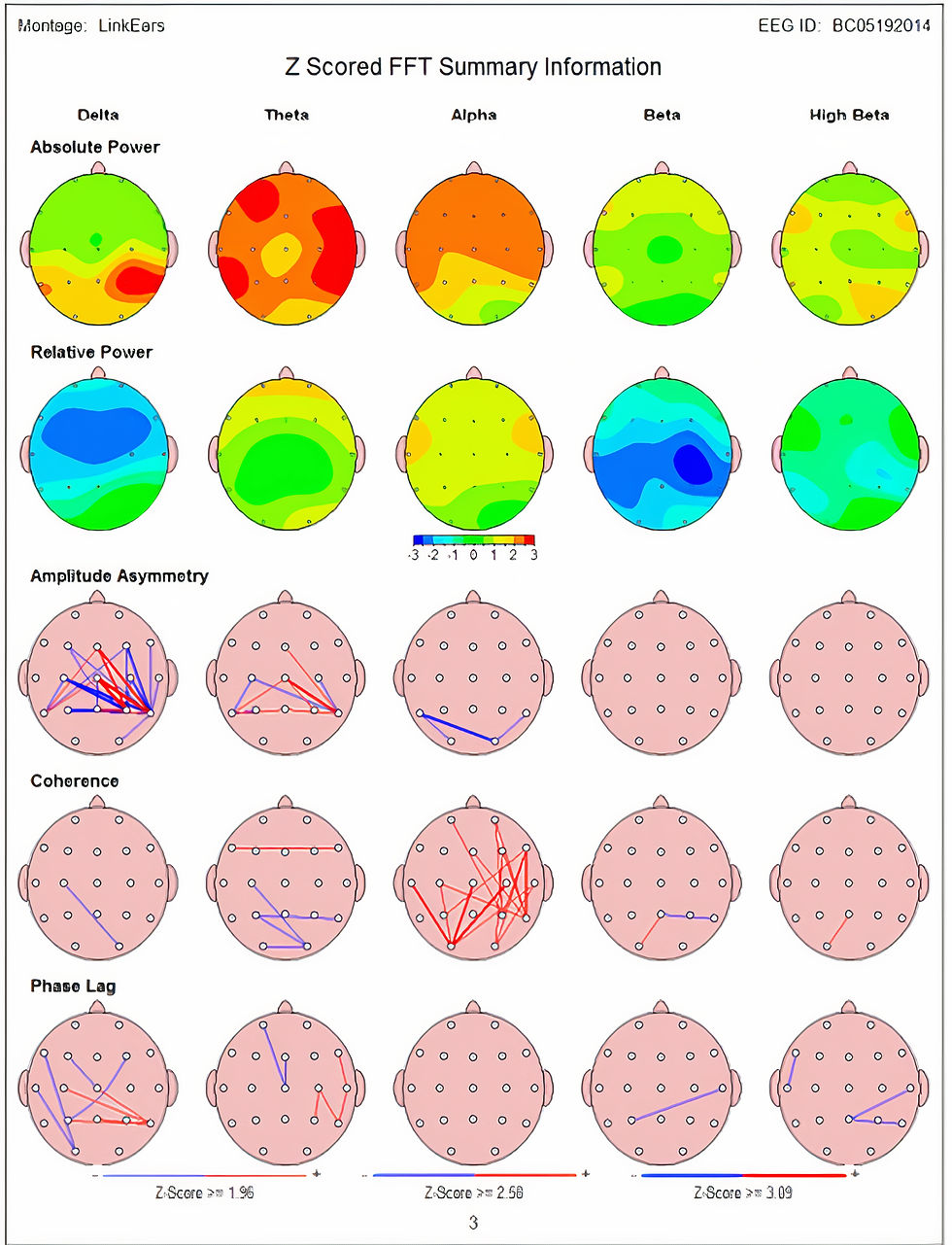

Quantitative EEG (qEEG) assessment is a promising approach for identifying TBI changes in the brain. Unlike structural imaging, the qEEG can detect brain function and communication changes. This distinction is important because persisting cognitive symptoms and fatigue may be related to reduced neural communication efficiency resulting from TBI (Levine et al., 2008). The qEEG allows clinicians to determine the consequences of mTBI and track changes due to spontaneous healing and treatment. qEEG measures that are associated with traumatic brain injury often are metrics related to neural communication, such as coherence and phase (Thatcher et al., 1989). However, localized changes shown by qEEG can be seen with more severe TBI. Although brain damage from moderate-severe closed TBI usually involves the frontotemporal regions, localized, as contrasted with diffuse damage, can be quite heterogeneous.

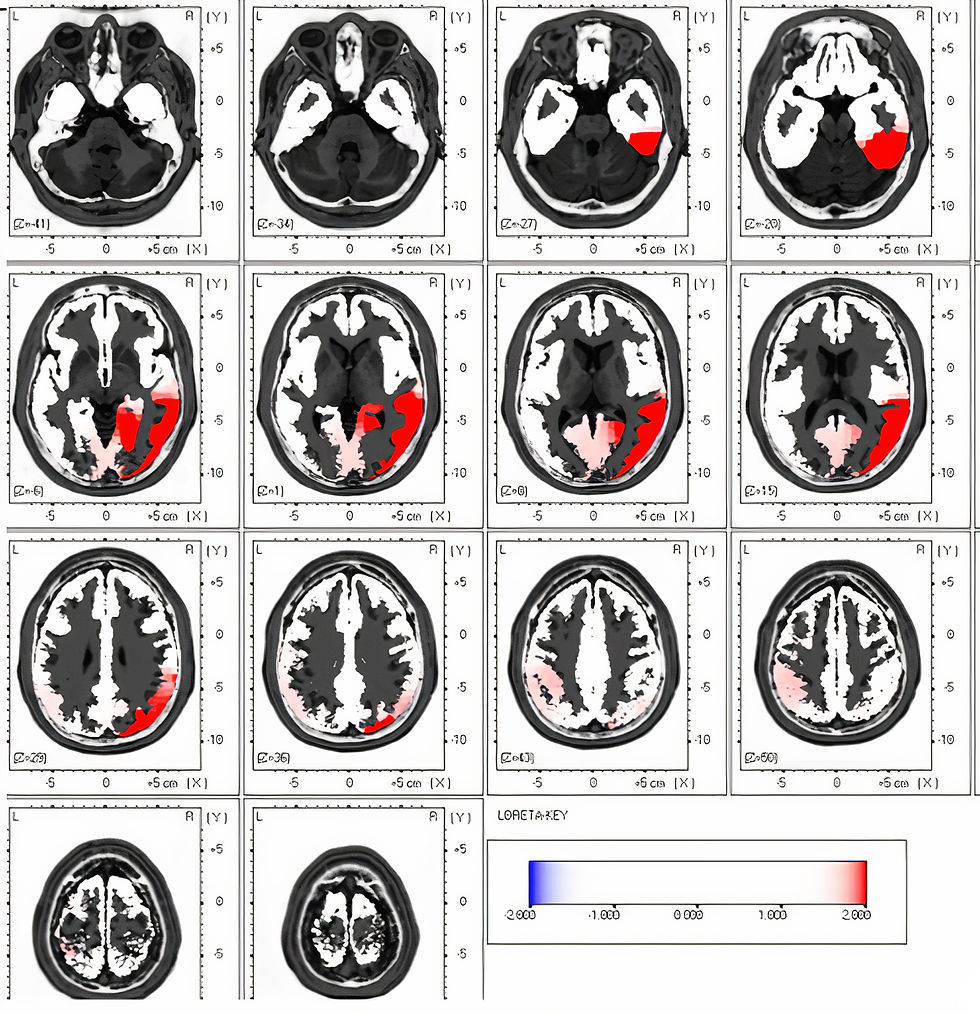

The images (courtesy Mary Tracy, PhD, Northern California Neurotherapy) below show LORETA imaging analysis of an individual struck in the face by a man using a closed fist. The first image is derived from an EEG recording done 4 days post-assault. The red areas represent activity at 2 Hz, in the delta frequency range that exceeds 2 standard deviations (SD) greater than expected according to a reference database of typical age-matched subjects. The images show what is likely a contra coup injury in the right posterior temporal/parietal/occipital cortices resulting from the impact of the brain on the inside of the skull due to the punch from a right-handed individual striking the center-left front of the face and forehead.

The second image shows a qEEG recording of the same individual 2 months post-injury using the same frequency and SD scale, confirming the resolution of the initial findings. There were no interventions beyond rest and a leave of absence from work (Mary Tracy, personal communication).

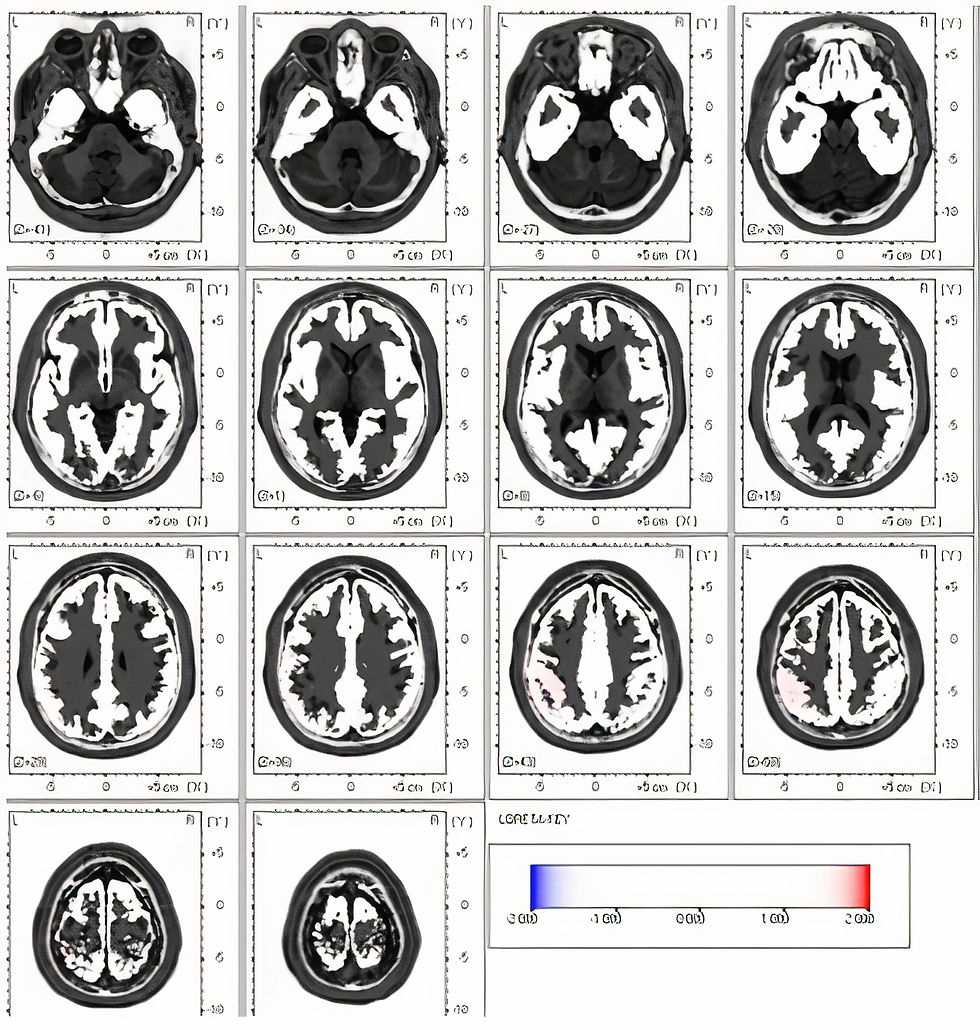

The images below (Koberda, 2015) are from an individual with multiple concussions with an additional diagnosis of ADD and behavioral problems. The first image's top row shows topographic statistical maps. The green color shows typical values within 1 SD, the yellow color within 2 SD, and the red color between 2.5 - 3 SD, indicating excess delta, theta, and alpha activity.

The second image shows the same client after 10 neurofeedback (NF) training sessions, where much of the atypical activity has resolved.

A Rationale for Q-EEG-Guided Neurofeedback

TBI reduces brain function efficiency, as seen in reduced processing speed and attentional impairments (e.g., focused, sustained, selective, alternating, and “divided” attention). Because cognitive functions such as language, visuospatial construction, and reasoning integrate multiple more “basic” functions like attention, the effects of mTBI on attention can indirectly affect other cognitive domains. Some have compared brain function following TBI to highway flow during construction when high flow funnels down from many to just one or two lanes. This results in less smooth and efficient flow, with traffic moving in an accordion-like stop-and-start manner with occasional fender benders.

After TBI, the experience can subjectively feel like one’s mind is similarly acting in a halting fashion, jumping around, and alternatingly freezing, overheating, and melting down because greater mental effort is required for tasks that were formerly easy because of their overlearned efficiencies. Alternating and divided attentional deficits can affect cognitive and emotional domains. During even mild injury events such as relatively low-speed impact or acceleration/deceleration injuries from car accidents or sports or other events such as falls, neurons in the brain can experience some mechanical stress. Geddes-Klein and colleagues (2006) found that the deformation of the brain during mTBI resulted in a complex type of strain throughout the brain tissue. This was more pronounced when the forces occurred from multiple directions, such as when automobiles impacted each other or objects multiple times during a single crash. This also occurs, for example, when several players impact an opposing player during a football tackle.

Chaves and colleagues (2021) found significant changes in the accumulation of amyloid β peptide, which is often implicated in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, following the mechanical stresses experienced during mTBI. Yap and colleagues (2017) found changes in even very mild mTBI events, specifically in the alteration of axonal signaling functions related to collapsed axonal growth cones.

These findings suggest that, although imaging studies such as CT, MRI, fMRI, and DTI do not identify such minute injuries, they are nonetheless present and may contribute to the self-reports of many mTBI patients of continuing cognitive deficits.

Neurofeedback is an efficacious and specific treatment for ADHD, which is characterized by prominent attentional and executive dysfunction. If NF helps ADHD’s attentional and executive impairments, it might address similar impairments post-mTBI. However, similar symptoms do not guarantee the same underlying mechanisms. Therefore, NF's mechanism of action in ADHD and mTBI may differ.

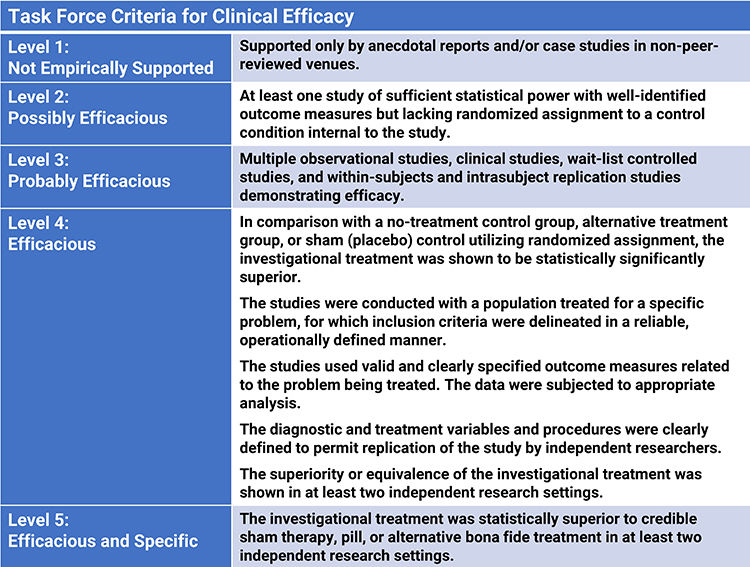

Foster, Foster, and Gross (2023) assigned a level-3 rating of probably efficacious to neurofeedback for TBI based on four randomized controlled trials (Ayers, 1993; Keller, 2001; Polich et al., 2020; Schoenberger et al., 2001) in Evidence-Based Practice for Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

The authors concluded that the diverse nature of TBI requires tailored treatments. NF will be most successful when it addresses specific client symptoms. Quantitative Electroencephalography (qEEG) and other functional neuroimaging techniques allow clinicians to correlate presenting complaints with neural network anomalies more precisely.

Promising NF training advances include operant conditioning utilizing real-time normative database comparisons (z-score training) and training several measures concurrently (e.g., inhibiting 4-7 Hz and rewarding 15-18 Hz activity). EEG tomography through Low-Resolution Electromagnetic Tomography Analysis (LORETA) offers greater training specificity and TBI treatment customization.

Clinicians can supplement mTBI improvement evaluation with the pre-post assessment of various measures of attention (e.g., continuous performance test, N-back, Auditory Consonants Trigrams, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test).

The qEEG can be helpful in identifying the physiological changes in brain function resulting from even a single mTBI as well as from multiple mTBI events. It can also be used to show the resolution of such changes. The qEEG is especially helpful following mTBI and more severe forms of traumatic brain injury in guiding neurofeedback to train the brain to correct atypical and dysregulated patterns, ideally to recover functions impaired by such injuries. Based on four randomized controlled trials, NF is probably efficacious in treating TBI.

Glossary

Concussion: A type of mild traumatic brain injury caused by a blow or jolt to the head, causing the brain to move rapidly inside the skull.

Contra coup injury: A type of traumatic brain injury. When the head sustains a forceful impact, the brain can hit the opposite side of the skull (the side opposite to where the impact occurred), resulting in damage.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI): A type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that measures the diffusion of water molecules in tissues to produce images of the brain. In N

NF, DTI can provide valuable insights into the neural pathways and integrity of the brain's white matter, assisting in identifying areas of damage, especially following a traumatic brain injury.

Level-2 rating of possibly efficacious: At least one study of sufficient statistical power with well-identified outcome measures but lacking randomized assignment to a control condition internal to the study.

Level-3 rating of probably efficacious: Multiple observational studies, clinical studies, wait-list controlled studies, and within-subjects and intra-subject replication studies show a treatment is probably efficacious.

Low-Resolution Electromagnetic Tomography Analysis (LORETA): A computational method used in EEG biofeedback that provides three-dimensional images of the electrically active regions of the brain. It helps to identify the specific locations in the brain where irregular electrical activity occurs. This information can guide the application of NF interventions.

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI): Also commonly referred to as a concussion, mTBI is a type of brain injury often resulting from a shock or blow to the head, causing a temporary disruption in normal brain function.

Quantitative EEG (qEEG): Digitized statistical brain mapping using at least a 19-channel montage to measure EEG amplitude within specific frequency bins.

Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI): A specialized type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that leverages the variations in magnetic properties of different tissues to produce unique, high-resolution images. It's particularly effective for visualizing small veins, microhemorrhages, and iron deposits in the brain.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI): A form of acquired brain injury that occurs when a sudden trauma causes damage to the brain. It can range from mild (a brief change in mental status or consciousness) to severe (an extended period of unconsciousness or memory loss). NF can be part of a comprehensive rehabilitation strategy aimed at restoring cognitive and physical functions impaired by the injury.

Beauchamp, M. H., Beare, R., Ditchfield, M., Coleman, L., Babl, F. E., Kean, M., Crossley, L., Catroppa, C., Yeates, K. O., & Anderson, V. (2013). Susceptibility weighted imaging and its relationship to outcome after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Cortex, 49(2), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2012.08.015 Belanger, H. G., Tate, D. F., & Vanderploog, R. D. (2018). Concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. In J. E. Morgan & J. H. Ricker (Eds.), Textbook of clinical neuropsychology (2nd ed., pp 411-448). Routledge. Broglio, S. P., Eckner. J. T., Martini, D., Sosnoff, J. J., Kutcher, J. S., & Randolph, C. (2011). Cumulative head impact burden in high school football. J Neurotrauma, 28(10), 2069–2078. https://doi.org/10.1089%2Fneu.2011.1825

Chaves, R. S., Tran, M., Holder, A. R., Balcer, A. M., Dickey, A. M., Roberts, E. A., Bober, B. G., Gutierrez, E., Head, B. P., Groisman, A., Goldstein, L. S. B., Almenar-Queralt, A., & Shah, S. B. (2021). Amyloidogenic processing of amyloid precursor protein drives stretch-induced disruption of axonal transport in hiPSC-derived neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 41(49), 10034–10053. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2553-20.2021

Crisco, J. J., Fiore, R., Beckwith. J. G., Chu, J. J., Brolinson, P. G., Duma, S., McAllister, T. W., Duhaime, A.-C., & Greenwald, R. M. (2010). Frequency and location of head impact

exposures in individual collegiate football players. J Athl Train, 45(6), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-45.6.549 Foster, S. R., Foster, D. S., & Gross, M. N. (in press). Traumatic brain injury. In I. Z. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.). Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Geddes-Klein, D. M., Schiffman, K. B., & Meaney, D. F. (2006). Mechanisms and consequences of neuronal stretch injury in vitro differ with the model of trauma. Journal of Neurotrauma, 23(2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2006.23.193

Keller, I. (2001). Neurofeedback therapy of attention deficits in patients with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotherapy, 5(1–2), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v05n01_03

Koberda, J. L. (2015). LORETA z-score neurofeedback-effectiveness in rehabilitation of

patients suffering from traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurobiol 1(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.16966/2379- 7150.113

Levine, B., Kovacevic, N., Nica, E. I., Cheung, G., Gao, F., Schwartz, M. L., & Black, S. E. (2008). The Toronto traumatic brain injury study: Injury severity and quantified MRI. Neurology, 70(10), 771–778. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000304108.32283.aa

Peskind, E. R., Brody, D., Cernak, I., McKee, A., & Ruff, R. L. (2013). Military- and sports-related mild traumatic brain injury: Clinical presentation, management, and long-term consequences. J Clin Psychiatry, 74(2), 180-188. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12011co1c

Polich, G., Gray, S., Tran, D., Morales-Quezada, L., & Glenn, M. (2020). Comparing focused attention meditation to meditation with mobile neurofeedback for persistent symptoms after mild-moderate traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. Brain Injury, 34(10), 1408–1415. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1802781

Rosenfeld, J. V., McFarlane, A. C., Bragge, P., Armonda, R. A., Grimes, J. B., & Ling, G. S. (2013). Blast-related traumatic brain injury. The Lancet Neurology, 12(9), 882–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70161-3

Thatcher, R. W., Walker, R. A., Gerson, I., & Geisler, F. H. (1989). EEG discriminant analyses of mild head trauma. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 73(2), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(89)90188-0

Yap, Y. C., King, A. E., Guijt, R. M., Jiang, T., Blizzard, C. A., Breadmore, M. C., & Dickson, T. C. (2017). Mild and repetitive very mild axonal stretch injury triggers cystoskeletal mislocalization and growth cone collapse. PloS one, 12(5), e0176997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176997

Feedback

We value your feedback because we produce these posts for you. Please complete our brief survey to help us improve this service.

Quiz

Take a five-question exam on Quiz Maker to test your mastery.

Comments