5-Min Science: The Paradox of ADHD

- Zachary Meehan

- May 28, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 1, 2025

The Misnomer of Attention Deficit

How can someone be unable to focus on a 10-minute homework assignment but stay up all night playing video games, drawing characters from their favorite show, or reading about black holes?

This contradiction lies at the heart of ADHD—one of the most misunderstood mental health conditions. ADHD is widely recognized yet rarely well understood, even by clinicians. Many people acknowledge attention is involved at some level but ultimately respond to challenges as matters of laziness, inconsistency, or intelligence.

At its core, ADHD is not about lacking attention—it's about struggling to control it. And that one concept—dysregulated attention—can explain nearly every challenge individuals with ADHD face.

Understanding Attention

To understand ADHD, it is helpful first to consider what attention means. In everyday conversation, we often describe attention as if it's a tool we deliberately control—like a computer mouse, something we point and click. But attention isn't that mechanical. Much of it is automated (Anderson, 2021; Lev-Ari et al., 2022), making it more like breathing.

You don't consciously think about every inhale and exhale, just as you don't actively monitor every sight and sound around you. Your brain handles most of this without your involvement—filtering, prioritizing, and suppressing information so you can focus on what matters (Bishop, 2008), such as finding the nearest bathroom. This background automation is essential; if we had to process every sound, every color, and every stray thought manually, we'd quickly become overwhelmed and burned out. In other words, much of your attention is outside of your control. What we often refer to as attention is the intentional effort making up a small part of the larger system.

For most people, attention works behind the scenes to keep them focused on what's relevant. Your body and brain are working right now to direct your attention. You intentionally follow the words on this page. At the same time, your brain automatically filters out the background noises of cars, birds, or the sensation of your clothes, even suppressing distracting thoughts like your upcoming work schedule. If you try, you may be able to switch your focus back and forth between these sensations with relative ease.

When Attention Regulation Breaks Down

Sometimes, this automated system gets disrupted. Think about a time when you could not sleep. The next day, you may have felt foggy, unmotivated, and sluggish, rereading the same sentence repeatedly as you nodded off. Just as muscles fatigue from a lack of sleep, your ability to regulate attention can also become fatigued (Liu et al., 2020). Adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, and regular exercise help maximize your capacity for attention, though these supportive measures alone usually do not fully resolve the challenges associated with ADHD. However, they demonstrate that attention regulation is not a constant process. Your ability to focus can fluctuate from day to day.

With ADHD, the brain's filtration and management system is chronically disrupted (Lin et al., 2015), meaning that struggles to regulate attention persist even with adequate sleep, nutrition, and exercise. Attention isn't missing. There is no genuine deficit; rather, the brain struggles to regulate when attention is engaged, what it focuses on, and how easily it lets go.

Neuroscience research suggests that this dysregulation involves atypical dopamine reward pathways, which influence the fluctuation of attention and motivation in an unpredictable manner (Tripp et al., 2024). This means that it is easier to pay attention to things that make you feel good. You may find it easier to read your favorite book series than to read tax law. What is the difference in these scenarios? You enjoy the book. For you, it may not matter that reading tax law would be more helpful than your favorite book series. You still cannot force yourself to read it with the same intensity or focus. People with ADHD experience this same problem, just to a greater degree.

Dysregulated Attention Affects Everyday Life

These difficulties extend beyond school and work, manifesting in almost every aspect of life. Imagine a child struggling to follow along with a story being read aloud but spending hours absorbed in a book about dinosaurs. Or an adult unable to sort through bills yet spending an entire weekend meticulously reorganizing the garage. These behaviors aren't merely a matter of selective attention or laziness; they signify the brain mismanaging attention—when it appears and how long it remains focused.

People with ADHD experience attention unpredictably. It might vanish during a lecture, spike during an argument, or intensely lock onto a single task while everything else fades away. These fluctuations appear inconsistent, but they're rooted in impaired executive functions—core cognitive skills such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibition, and planning —essential for planning, prioritizing, initiating, and completing tasks. When executive functions operate inconsistently, the result isn't a lack of effort but internal dysregulation.

Contextual Variability and Diagnosis

What makes ADHD harder to recognize is that symptoms shift based on context (Murray et al., 2019). More structured and predictable environments, such as classroom behavioral interventions and parental scaffolding, can mask impairments. A child might excel in structured classes but struggle during the unstructured chaos of summer vacation. Adolescents thriving in supportive high school environments may flounder in college when managing tasks independently.

Diagnosis often occurs when life's demands surpass their internal capacity, which is also influenced by gender, socioeconomic status, and cultural differences, further complicating timely recognition and support. For example, we often accept that toddlers are full of energy, cry when they are disappointed, and dislike sitting for longer than a few minutes. However, when that same toddler is just a year or two older, we expect them to sit for 6-8 hours per day in the kindergarten classroom. Although most children can successfully make the transition, many children with ADHD cannot.

Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC, 2013) reports that the average age of ADHD diagnosis was 5 years old for severe ADHD, 7 years old for moderate ADHD, and 8 years old for mild ADHD. In other words, teachers and parents may not notice that a child has a problem until the environmental demands (e.g., classroom expectations) exceed the child's ability to adapt.

Misunderstanding and Mismanagement

When misunderstood, and it is often misunderstood, ADHD is mismanaged.

Missed deadlines or procrastination are incorrectly attributed to a lack of motivation, creating cycles of frustration. An illustrative example may be the best teacher.

Jordan, a 13-year-old boy, rushes to school hastily. In math class, while the teacher explains how to divide by fractions, his mind drifts to the sound of the erasers scraping on paper or how to make his friend laugh. When he occasionally tunes in, he realizes others are almost finished with work he barely started—so he rushes through the worksheet, only to be told his work is sloppy and needs to be redone. In English class, the teacher asks for a late assignment he finished two nights ago with his mom's help. After some panicked rummaging, he gratefully finds it crumpled at the bottom of his backpack. By the time Jordan gets home, he's mentally drained. He sinks into the couch, trying to lose himself in his favorite show, not hearing his mom's voice from the kitchen until she walks in, frustrated. He jumps up to do the chores, but her sigh—"Why do I always have to remind you?"—makes his chest tighten. He whines, saying he didn't hear her, but she sighs and tells him to get started. The rest of the night is filled with corrections and checklists: stop making that noise, you need to try harder, wash your hands already, you didn't wash thoroughly, etc. Although his mom ends the day with a kind reminder that he can do better if he applies himself, Jordan lies in bed replaying every mistake, wondering what he's already forgotten for tomorrow.

Each time Jordan is reprimanded, reminded, or corrected, the behavior is fixed, but the underlying skill remains undeveloped. This isn't a motivation issue; it's a lack of creative problem-solving. From the outside, the child appears responsive only to nagging; internally, they feel a constant sense of failure. Effort increases under pressure, making up for the difference in attention for as long as they can maintain it. But like any muscle, the effort only works for so long. This strategy is ineffective without appropriate tools. Just as a child needs explicit instruction to master dividing fractions, adults require structured systems to organize their tasks effectively. ADHD treatment isn't just about inspiring motivation; it's about bridging intention and action.

Emotional Impacts

Living with ADHD involves experiencing a mismatch between desire and ability, leading to demoralization that gets compounded by well-intentioned loved ones (Peris & Miklowitz, 2015). Children with ADHD often face frequent corrections—"sit down, stop talking, focus"—but little praise, subsequently internalizing messages of inadequacy. Often, that means frequent criticisms about individuals' behaviors related to ADHD can persist and even worsen their symptoms (APA, 2016). If this pattern occurs frequently and persistently, it can even influence how people perceive themselves, others, and the world around them (Choi et al., 2022). Anxiety can emerge as a self-protective strategy, hyper-alertness developing to catch errors before they occur, eventually leading to exhaustion and burnout. Depression is also common, as continued struggles to achieve what comes easily to others can lead to low self-esteem, hopelessness, and guilt.

Emotional dysregulation, though not explicitly in diagnostic criteria, is common, disruptive, and painful (Sáez-Francàs et al., 2023). Most people move smoothly through emotions—disappointment, frustration—recovering as quickly as their attention can shift from problems to solutions. For individuals with ADHD, shifting emotional states can be extremely challenging. An anticipated event that gets canceled or a close friend that gets upset can lead to prolonged frustration or emotional spirals. Such reactions aren't immaturity but difficulties transitioning emotional attention from one state to another, increasingly recognized as central to the ADHD experience.

Supporting Individuals with ADHD

To address this, we must shift from asking, "Why aren't they trying harder?" to "What's missing?" What structures or supports could bridge the gap between knowing and doing? For example, take a step back the next time you notice your child forgot their homework on the table for the second day in a row. Instead of sighing and criticizing them, think about what might help them remember. If they cannot rely on their attention for the answer, consider a creative alternative, such as setting an alarm on their phone with a list of items they need to check each day before leaving for school.

This means replacing punishment with structure, judgment with understanding, and blame with support. Parents should provide scaffolding, teachers should implement predictable classroom systems, clinicians should address the emotional toll, and employers should measure outcomes rather than micromanage processes. If the attempts are not sufficient to address the issue, pivot and try something else. There are a host of creative solutions available on the internet, such as those supported by Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), if you are interested in brainstorming.

ADHD is not a character flaw but a neurological difference requiring different strategies. With appropriate support, individuals with ADHD can thrive creatively, insightfully, resiliently, and purposefully. Let's meet them where they are—and build a world that helps them move forward confidently.

Key Takeaways

ADHD is not a lack of attention but a chronic difficulty regulating it: individuals with ADHD struggle to control when attention starts, where it goes, and how long it stays, leading to inconsistent performance across tasks and settings.

Much of attention operates automatically: ADHD disrupts these background processes, such as filtering, prioritizing, and shifting focus—making everyday tasks unpredictably harder, even when motivation is high.

Emotional dysregulation is a central, though often overlooked, feature of ADHD: it contributes to prolonged frustration, sensitivity to setbacks, and difficulty recovering from emotional disruptions.

Misrepresenting people with ADHD as lazy or irresponsible leads to harmful responses: constant corrections or judgments can erode self-esteem and contribute to anxiety, depression, and burnout.

Support for ADHD must focus on structure and skill-building rather than punishment: bridge the gap between intention and action with systems, scaffolding, and compassion allows individuals with ADHD to thrive.

Glossary

ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder): a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity that interfere with functioning or development. The condition is marked more by dysregulation of attention than an actual deficit.

anxiety: a mood state characterized by excessive worry, nervousness, or fear, often in response to perceived threats or uncertainty. In ADHD, anxiety may develop as a compensatory mechanism to anticipate and prevent errors.

cognitive flexibility: the mental ability to switch between thinking about two different concepts or to think about multiple concepts simultaneously. Impaired in many individuals with ADHD, contributing to difficulties adapting behavior to new tasks or shifting attention.

depression: a mood disorder involving persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a lack of interest or pleasure in most activities. It often co-occurs with ADHD due to chronic frustration and perceived underachievement.

dopamine reward pathway: a network in the brain involving dopamine neurotransmission, crucial for motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement learning. Atypical functioning in this system is implicated in the motivational and attentional fluctuations in ADHD.

dysregulated attention: a core concept in ADHD referring to inconsistent control over attentional focus—difficulty initiating, sustaining, or shifting attention regardless of intention or motivation.

emotional dysregulation: difficulty in managing emotional responses and returning to a baseline emotional state after stress. Common in ADHD, even though it's not a formal diagnostic criterion.

executive functions: higher-order cognitive processes—including working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibition, and planning—that regulate goal-directed behavior. Often impaired in ADHD, leading to inconsistent performance and poor task management.

inhibition: the ability to suppress irrelevant or inappropriate responses. Deficits in inhibitory control are a hallmark of ADHD and contribute to impulsivity.

neurodevelopmental disorders: a class of disorders that begin in the developmental period and involve functional impairments in personal, social, academic, or occupational areas. ADHD falls under this category.

planning: the cognitive process of setting goals and determining the best way to achieve them. Impairments in this area are frequently seen in individuals with ADHD.

scaffolding: a support strategy used in educational and therapeutic contexts to aid skill development by providing temporary structures that are gradually removed as competence increases. Often applied in ADHD interventions to bolster executive function.

self-regulation: the ability to monitor and modulate behavior, emotions, and thoughts in pursuit of long-term goals. Individuals with ADHD typically struggle with self-regulation due to underlying executive function deficits.

working memory: a component of executive function that involves holding and manipulating information over short periods. Often compromised in ADHD, affecting task follow-through and multi-step instructions.

References

Anderson, B. A. (2021). An adaptive view of attentional control. American Psychologist, 76(9), 1410.

American Psychological Association. (2016, February 22). Persistent ADHD associated with overly critical parents. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2016/02/adhd-critical-parents

Bishop, S. J. (2008). Neural mechanisms underlying selective attention to threat. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1129(1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1417.016

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Key findings: Trends in the parent-report of health care provider diagnosed and medicated ADHD: United States, 2003–2011. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD). https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/ncbddd/adhd/features/key-findings-adhd72013.html

Choi, W. S., Woo, Y. S., Wang, S. M., Lim, H. K., & Bahk, W. M. (2022). The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in adult ADHD compared with non-ADHD populations: A systematic literature review. PloS one, 17(11), e0277175. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277175

Lev-Ari, T., Beeri, H., & Gutfreund, Y. (2022). The ecological view of selective attention. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16, 856207. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.856207

Lin, H. Y., Tseng, W. Y. I., Lai, M. C., Matsuo, K., & Gau, S. S. F. (2015). Altered resting-state frontoparietal control network in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 21(4), 271-284. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135561771500020X

Liu, Q., Liu, Y., Leng, X., Han, J., Xia, F., & Chen, H. (2020). Impact of chronic stress on attention control: Evidence from behavioral and event-related potential analyses. Neuroscience Bulletin, 36, 1395-1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-020-00549-9

Murray, A. L., Ribeaud, D., Eisner, M., Murray, G., & McKenzie, K. (2019). Should we subtype ADHD according to the context in which symptoms occur? Criterion validity of recognising context-based ADHD presentations. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 50, 308-320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0842-4

Peris, T. S., & Miklowitz, D. J. (2015). Parental expressed emotion and youth psychopathology: New directions for an old construct. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46, 863-873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0526-7

Soler-Gutiérrez, A. M., Pérez-González, J. C., & Mayas, J. (2023). Evidence of emotion dysregulation as a core symptom of adult ADHD: A systematic review. Plos one, 18(1), e0280131.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280131

Tripp, G., & Wickens, J. R. (2024). The dopamine hypothesis for ADHD: An evaluation of evidence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1492126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1492126

About the Author

Zachary Meehan earned his PhD in Clinical Psychology from the University of Delaware and serves as the Clinic Director for the university's Institute for Community Mental Health (ICMH). His clinical research focuses on improving access to high-quality, evidence-based mental health services, bridging gaps between research and practice to benefit underserved communities. Zachary is actively engaged in professional networks, holding membership affiliations with the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) Dissemination and Implementation Science Special Interest Group (DIS-SIG), the BRIDGE Psychology Network, and the Delaware Project. Zachary joined the staff at Biosource Software to disseminate cutting-edge clinical research to mental health practitioners, furthering his commitment to the accessibility and application of psychological science.

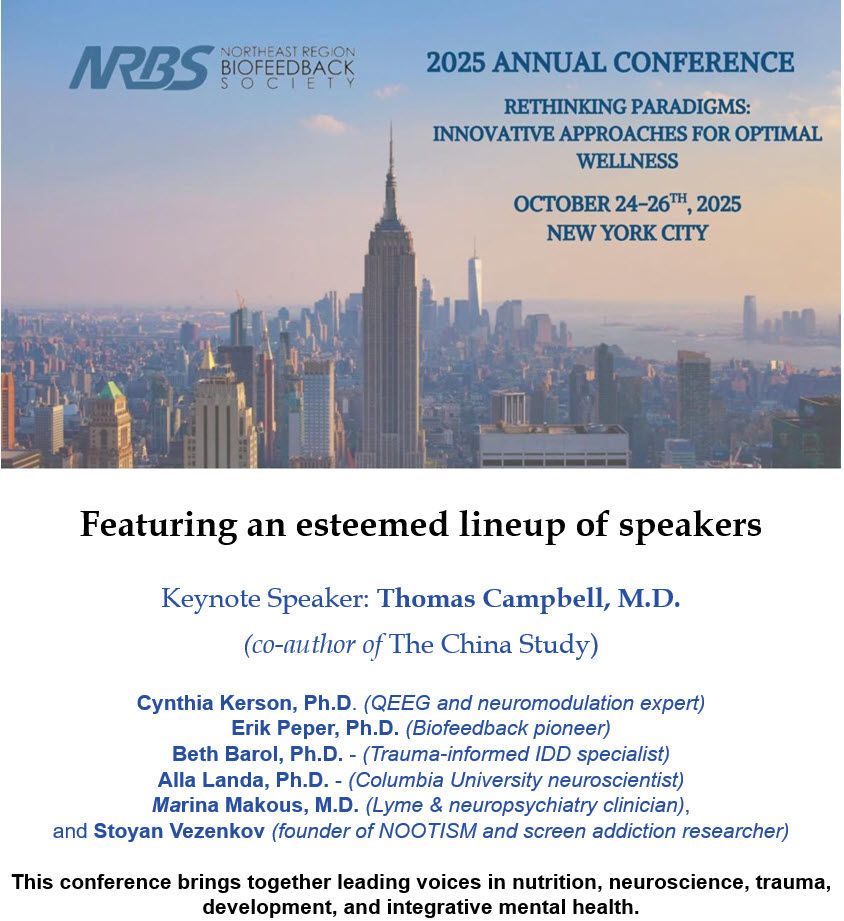

Support Our Friends

Excellent treatment of the complex and often frustrating set of issues that have become lumped into the category of ADHD. Should be read by every parent, teacher, health care professional and employer.